I. Introduction

As environmental problems become more prominent, the conservation and management of marine living organisms, such as whales, become an increasingly hot debate internationally. The Whaling in the Antarctic case[1] showcases the tensions that arise for the jurisprudence of international law concerning environmental protection and state sovereignty. The significance of this case is broad, ranging from clarification on the scope of “scientific research” under Article VIII of International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) to states compliance to international treaty obligation and giving “due regard” to non-binding commitments.[2]

The programme under review sparked international debates on if Japan was conducting whaling operations under the guise of “scientific research”, leading to Australia filling a case to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) (from here on: the court). The concerns were about the potential misuse of exceptions to the convention and how interpretations of legal formulations could be used to undermine international conservation efforts.

This case is not only significant for the clarification on environmental issues, but also for the influence the judgement has on holding states accountable for obligations they have under specific treaties. It shows how international courts handle complex cases on environmental ethics, scientific questions, and the boundaries of treaties.

The structure of this case note will be going through the factual and legal background and the legal reasoning of the judgement before the critical assessment regarding the duty to cooperate and giving “due regard”.

II. The Factual Background

The Whaling in the Antarctic case originated on 31 May 2010 as Australia submitted an application to the court. The application challenged Japan’s whaling activities under the JARPA II program claiming that these activities violated Japan’s obligations under the ICRW. The alleged violations by Japan included the moratorium on commercial whaling and the provision establishing the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary.[3]

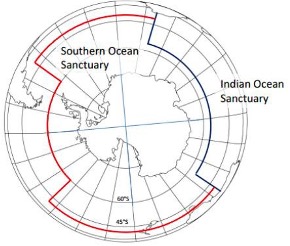

Japan has a long history of whaling, including relying on it for food security and cultural significance[4], and is one of the current whaling nations, next to Norway and Iceland. These nations exist even though commercial whaling was banned in 1986 when a new moratorium,[5] as well as two whale sanctuaries, was introduced by the International Whaling Commission (IWC)[6]. One of the sanctuaries is the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary[7], where Japan conducted its JARPA II programme.

Figure 1. Scope of Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary (red) and Indian Ocean Whale Sanctuary (blue)[8]

Japan’s JARPA II program was launched 2005 in the light of conducting scientific research. JAPRA II had 4 main research objectives including “monitoring of the Antarctic ecosystem, modelling competition among whale species and future management objectives, elucidation of temporal and spatial changes in stock structure, and improving the management procedure for Antarctic minke whale stocks”. Both the use of lethal and non-lethal methods was used, and the sample sizes were annually 50 for fin and humpback whales and 850 for Antarctic minke whales, +/- 10%, double that of the preceding JARPA programme.[9] There were multiple controversies on whether this programme had a scientific nature or not, ultimately leading to Australia’s objection. Australia initially attempted to address the issue diplomatically, using IWC negotiations as one method, but upon multiple failed attempts submitted the dispute to the court.

III. The Legal Background

The court has jurisdiction in this case because of both the parties’ declarations under article 36(2) of the ICJ statue. This combined with their obligations under the ICRW and its schedule[10] gave the court the task of interpreting the treaty in the context of this dispute. An intervening state was New Zealand[11], highlighting the importance of treaty interpretation for whale conservation.

The legal background to the case will be done by explaining the relevant provisions. Firstly, Article VIII of the ICRW, which was established in 1946, allows member states to kill, take, or treat whales outside of commercial restriction for the purpose of scientific research, under special permits from governments. The ICRW established the IWC, the body overseeing the conventions implementation. The IWC established the two whale sanctuaries to which the restrictions did not apply under Article VIII of the ICRW if conducted “for the purpose of scientific research”.

Secondly, the IWC established the 1986 moratorium on commercial whaling, banning commercial whaling on all species, which remains in place today. Japan was initially exempt from this ban as it immediately lodged a legal objection to the moratorium. However, it later withdrew this objection and conducted whaling, in Japan’s view, in accordance with Article VIII of the ICRW, provoking international criticism.

The interpretation of ICRW can be done in different ways because of the flexible language the treaty uses. This leads to different views on members states obligations. Australia claimed that Japan violated the IWC moratorium through the misuse of Article VIII of the ICRW and the definition of “for purpose of scientific research”. Japan claimed that it followed international law with the JARPA II program. The court therefore had two main legal question to interpret.

- Whether the JARPA II program qualifies as “for the purpose of scientific research” under Article VIII of ICRW.

- Whether the permits issues under JARPA II violated other obligations under the ICRW, such as the moratorium on commercial whaling and sanctuary restrictions.

IV. The Legal Reasoning of the Judgement

A contextual approach was used in the legal reasoning of the court, interpreting Article VIII in connection to the objectives of the ICRW, conservation and regulation of whaling, rather than relying solely on the text. The interpretation of Article VIII was deemed to be neither restrictive nor expansive, adopting a balanced approach.[12]

The court asserted that Article VIII was as an integral part of the convention while also acknowledging that there is an exemption.[13][14] It clarified that the issuing of special permits is not absolute to the state, and that Article VIII gives the ICRW the liberty to reject the issuing of such a special permit. Whether whaling is “for the purpose of scientific research” can therefore not depend exclusively on the authorizing states perception.[15]

The court decided to use an objective standard of review. Assessing: (1) whether JARPA II involved scientific research and (2) whether the “killing, taking, and treating of whales” is “for the purpose of” that “scientific research”.[16] The court emphasized that state parties must cooperate with the IWC to explore alternatives to the lethal-methods, shining light on the duty to cooperate.[17] The court considered JARPA II’s design and interpretation in relation to the scientific objectives, if they were reasonable or not, when evaluating the “for the purpose of” wording.[18][19]

In the assessment of the use of lethal methods, the court considered three points.[20] (1): Feasibility: the court contends that non-lethal methods are indeed feasible for some of the data that JARPA II collected.[21] (2): Reliability and value of data collected: the court found that it was essential to look at the decision for lethal methods, as it not find any basis that lethal methods were unreasonable. (3): Whether the objectives could be met using non-lethal methods: the court clarifies that under IWC resolution and Guidelines state parties are urged to consider whether non-lethal means can accomplish the said research goals. The court concludes that there is insufficient examination of the viability of employing non-lethal means to accomplish the JARPA II research objectives. The court therefore find it challenging to balance this with Japan’s duty to give due regard to the IWC resolutions and guidelines.

The court concluded that regarding the application of Article VIII of the convention to JARPA II the programme was lacking. Firstly, the target sample sizes were found not reasonable to the scientific objective of the programme. Secondly, the process used to determine the different sample sizes was thought to lack transparency[22]. The JARPA II programme can be considered as scientific research, however, the design and implementation are not reasonable to the stated scientific objectives and therefore the court finds that the permits grated were not “for the purpose of scientific research”, as would be considered an exception to the schedule under Article VIII of the convention. The court concluded that Japan breached three provisions[23] and ruled that JARPA II was not for scientific purposes.[24]

V. Critical Assessment

The Whaling in the Antarctic case is a landmark case that shows a shift to a new paradigm where the core issues of cases are inherently environmental.[25] An interesting discussion is the broader impact this judgement has to the development of international environmental law. The court determined that Japan had a duty to give “due regard” to IWC resolutions and guidelines when designing the relevant programme, JARPA II. The court determined this because of the duty to cooperate that can be found as an integral part of the ICRW.[26] Judge Charlesworth emphasizes, in her separate opinion, the substantive nature of the duty to cooperate, highlighting specific actions required under paragraph 30 of the ICRW Schedule.[27] [28]

The IWC resolutions and guidelines are non-binding and therefore “soft law”, and the emphasis that the court gave to the “due regard” of these non-binding instruments raises the legal significance for these types of instruments. This being a landmark judgement gives the approach a broader implication for other instruments within international regimes. Showing not only that the recommendations of the international organisations are of importance, but also that states inherently have a duty to cooperate even in non-binding legal instruments. I agree with this clarification from the court, especially in the evolving nature of environmental problems. The duty to give due regard and the duty to cooperate are essential in conservation, and therefore critical for environmental law. The protection of the environment can be ensured if all states must comply with non-binding agreements, even the ones to which they are not parties of.

In the separate opinion of Judge Charlesworth Japan was criticized for failing to meet the duty to cooperate, indicating a lacking in enforcement mechanisms for the duty to cooperate.[29] This highlights a conflict between the sovereignty of states, and the international cooperation on environmental issues. However, as Young and Sullivan mention “rather than threatening sovereignty, the Court’s expectation that states have ‘due regard’ allows for a more nuanced and sophisticated understanding of it.[30] Wold instead raises the question of traditional sovereignty and if the duty to cooperate inherently declines sovereignty, as it will no longer be absolute but shaped by international organisations. The interconnected world frames questions on the evolving nature of sovereignty, especially in the cooperation of protection of the marine environment.[31] In this case there is a clear challenge of transitional notions of sovereignty, with the judgement potentially shifting power relations between states and international organisations. I believe that this is an essential step in international environmental law. The sovereignty of states must be challenged to protect the environment, and inherently humankind, from non-sustainable activities.

Professor Chris Wold contributes more to the discussion regarding the duty to cooperate by relating it to a broader customary international law, and the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)[32], to which Japan is a party. This would mean not only grounding the duty to cooperate in specific treaties, like the ICRW, as the court did. Wold exemplifies this through Article 197 of UNCLOS that imposes an obligation to states for cooperation in matters concerning the marine environment.[33] This broader perspective shows how the duty to cooperate can hold states accountable, even when not party to a specific treaty.[34]

VI. Conclusion

Concluding, the Whaling in the Antarctic case is a landmark case in international environmental law. The evolving nature of soft law instruments and the duty to cooperate and the legal significance this has to the conservation of whale stocks was emphasised in the court ruling. This case can be seen as a precedent for future cases as it set an emphasis on the “due regard” that states must consider in even non-binding resolutions. The principles and judgment of this case will have a significant effect on the behaviour of states concerning conservation of marine mammals, and the shaping and development of international law.

[1] Whaling in the Antarctic (Australia v Japan: New Zealand intervening) (Judgement) [2014] ICJ Rep 226.

[2] Margaret A Young and Sebastian Rioseco Sullivan, ‘Evolution through the Duty to Cooperate: Implications of the Whaling Case at the International Court of Justice’ (2015) 16 Melbourne Journal of International Law 311.

[3] Whaling in the Antarctic (n 1).

[4] “Whaling Nations Should Take a Stand as ‘activists’ Meddle with Food Culture: Whaling Today.” Whaling Today | New perspectives on an old debate, March 31, 2022. https://featured.japan- forward.com/whalingtoday/2020/09/18/history-of-japanese-whaling-modern/.

[5] The introduction of the moratorium was because of multiple species of whales nearly being driving to extinction due to excessive whaling.

[6] CNN, ‘Japan Launches New Whaling Mothership as Industry Faces Uncertain Future’ (30 May 2024) https://edition.cnn.com/2024/05/30/asia/japan-whaling-mothership-kangei-maru-intl-hnk/index.html accessed 05 December 2024.

[7] “The Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary is in the water surrounding the entire continent of Antarctica and hosts dozens of whale species, including humpbacks, blue whales, and fin whales. It was established by the IWC in 1994 to protect whale species after centuries of hunting”. For more details, see CNN, ‘Japan Launches New Whaling Mothership as Industry Faces Uncertain Future’ (30 May 2024) https://edition.cnn.com/2024/05/30/asia/japan-whaling-mothership-kangei-maru-intl-hnk/index.html accessed 7 December 2024.

[8] International Whaling Commission, Southern Ocean Management Plan (IWC 2020) https://iwc.int/document_3713accessed 05 December 2024.

[9] International Cetacean Research Centre, Questions and Answers about Whaling (ICR 2024) https://www.icrwhale.org/QandA2.html accessed 01 December 2024.

[10] This is the set of detailed regulations attached to the ICRW, which IWC can amend to manage whaling activities. It includes provisions such as setting quotas, designating whale sanctuaries, and regulating hunting methods.

[11] New Zealand intervened under Article 63 of the ICJ Statute to support Australia’s arguments.

[12] Whaling in the Antarctic (n 1), [58].

[13] This exemption includes the obligations under the schedule of the moratorium relation to factory ships, if the whaling is conducted under a special permit.

[14] Whaling in the Antarctic (n 1), [55], [29].

[15] ibid [61].

[16] ibid [67].

[17] ibid [83].

[18] The different ways of assessing this included: decision on the use of lethal methods, scale of lethal sampling, methodology to selection of sample sizes, target sample v. actual sample, time frame, scientific output and “the degree to which a programme co-ordinate its activities with related research projects.

[19] Whaling in the Antarctic (n 1), [88].

[20] ibid [132].

[21] ibid [133].

[22] An example of this would be the decision to double the sample size from the precedent programme JARPA.

[23] These provisions being: the obligation to respect zero catch limits for the killing for commercial purposes of whales from all stocks, the factory ship moratorium, and the prohibition on commercial whaling in the Southern Ocean Sanctuary.

[24] Whaling in the Antarctic (n 1), [227].

[25] Dario Piselli, ‘The Whaling in the Antarctic Case: A Landmark Judgment and Its Potential Implications’ (Undergraduate Thesis, Università degli Studi di Siena, Department of Law).

[26] Whaling in the Antarctic (n 1), [26].

[27] Judge ad hoc Charlesworth, Separate Opinion in Whaling in the Antarctic (Australia v Japan: New Zealand intervening) [2014] ICJ Rep 226, 359, [15].

[28] Paragraph 30 of the Schedule provides that a state authorising special permits shall provide the secretary to the IWC with the proposed scientific permits before they are issues. This is to allow review and potential comment on them.

[29] Judge ad hoc Charlesworth (n 27), [17].

[30] Young and Sullivan (n 2) 28.

[31] Chris Wold, “Legal Opinion Concerning Japan’s Duty to Cooperate with the International Whaling

Commission with Respect to Any Resumption of Commercial Whaling,” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2019, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3410248.

[32] Chris Wold (n 30) 3-5.

[33] United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (adopted 10 December 1982, entered into force 16 November 1994) 1833 UNTS 3, [197].

[34] ibid 3-5.